Published: December 27, 2025

I recently fell in love with a paper by Andrew Gordon Wilson entitled "Deep Learning is Not So Mysterious or Different" which I not only find to be a great title but but also a deeply thought-provoking piece of work. Essentially, Wilson argues that the strange generalization behaviour observed for LLMs (or in fact any large transformer architecture) of double descent is in fact not so strange after all given you can observe the very same phenomenon for much simpler models too.

Consider an arbitrarily large polynomial that is intended to fit a data set much smaller than the order of the polynomial. The only constraint being that higher order coefficients are weighted less (i.e. regularized more) than the lower order coefficients. This polynomial too will display double descent (as well as overparametrization and benign overfitting, all birds of one feather) just like any old transformer.

In fact for this behaviour to occur at all we only need two requirements: (a.) a flexible model that can fit many different distributions of the training data (i.e. including overfitting and fitting the noise); and (b.) a simplicity bias, i.e. essentially following Occam's razor. Imagine a data set consisting of points on more or less a straight line. The model could find enormously complicated higher order functions that fit this data, after all, it has the parameters to do so. But it will converge to simple two parameter model (i.e. linear regression or straight line) because, yes, it fits the data but also because it incurs the smallest penalty.

Wilson himself gives a molecular example: a soft bias for rotation equivariance for example empirically proved to work as well as a hard constraint. This makes perfect sense if we assume that the model again learns the simplest solution to fit the data, in this case, a rotationally equivariant representation. Such a flexible approach will then outperform a hard constraint if the data only contains approximate or no symmetries.

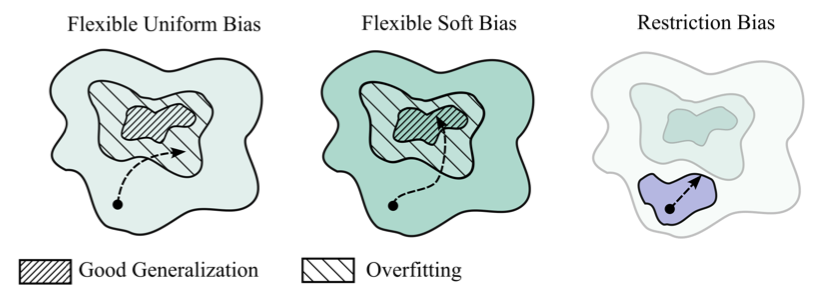

Wilson contrasts regularization techniques that make use of restriction biases, i.e. ruling out certain parts of the hypothesis space from the get-go, with models simply using a soft inductive bias. As Wilson writes, "[...] there is no need for restriction biases. Instead, we can embrace an arbitrarily flexible hypothesis space, combined with soft biases that esxpress a preference for certain solutions over others [i.e. simpler over more complex ones], without entirely ruling out any solution".

Clearly, transformers, LLMs, CNNs and so forth, follow Occam's razor. The question now no longer is why they show this double descent behaviour but rather why they have this simplicity bias at all and where in the architecture this originates. You also don't need to trust just double descent as evidence for their simplicity bias. Empirically, analyzing the effective parameters a model requires, it could be shown that larger models need fewer effective parameters than small models. In fact, the success that model distillation is having, i.e. the fact that we can train a smaller model on the output of larger models and recreate a very large part of its performance, suggests already that one doesn't need all the parameters of these large models to "memorize" the data or even just store their complicated world model. A much smaller, i.e. more compressed, version will do. Yet it seems we need the size of these models during training to arrive at this simpler solution. Clearly, there must be an avenue for optimization here and it interestingly runs somehow contrary to our typical "scaling orthodoxy". Put differently, if the small model is enough during inference, why should there not be a training methodology that arrives at this performance but using way fewer parameters (and hence compute)?

Many old school frameworks to describe generalization fail to accurately reflect this such as Rademacher complexity and VC-bounds. They fail because they explicitly penalize the size of the hypothesis space. Yet we just learned that this is precisely not the problem! Implicitly, both Rademacher and VC argue for restriction rather than soft inductive biases, which does not tend to be accurate. Instead, Wilson argues for using the Kolmogorov complexity which is the lengths of the shortes program that produces a hypothesis h for a fixed programming language. The Kolmogorov complexity can be calculated from just knowing the number of bits needed to represent the hypothesis h. Note that we have not made any assumptions about the distribution of desirable solutions (we could be more specific and include this via PAC-Bayes approaches) nor have we considered the actual size of the model at all, rather, we simply looked at how compressible its resulting world model is. Given this framework, even a very large model with extremely low training loss can achieve strong generalization if the trained model has small compressed size:

\[ expected~loss \leq training~loss + Kolmogorov~complexity\] Embracing flatland and the bliss of dimensionalitySome of the deepest insights to me come from looking at these findings from a Bayesian perspective, which Wilson had actually done in a previous paper in 2022 "Bayesian Deep Learning and a Probabilistic Persepective on Generalization". In that paper, Wilson and Izmailov argue for the preeminence of marginalization to understand inductive bias and why some models perform better than others. The marginal likelihood says how likely it is that we would sample the data \(\mathcal{D}\) given a prior over parameters \(p(w)\) which induces a distribution over models \(p(\mathcal{M})\), i.e.

\[ p(\mathcal{D}|\mathcal{M}) = \int p(\mathcal{D}|\mathcal{M}, w)p(w)\, dw\]Wilson and Izmailov then define the inductive bias of a model as just that: the distribution of the support or \(p(\mathcal{D}|\mathcal{M})\), i.e. which hypotheses are supported and which are supported more than others. A good model hence might have very large support but has an inductive bias such that the right hypotheses (e.g. an equivariant solution over a non-symmetric one) get favoured. If we look at the probability mass of that inductive bias, the majority of the distribution will be at the correct hypothesis, in other words, sampling from this distribution means we're much more likely to get back our data set. Compare this to a distribution with the same support but that is much flatter (i.e. no inductive bias at all), sampling from this distribution will only gives us a small chance of recovering our original data set.

We can now understand how Bayesian marginalization actually implicitly enforces simplicity: Simpler solutions will have more probability mass at the places of the actual data, i.e. the marginal likelihood of sampling our data set from such a distribution is much higher. In other words, maximizing marginal likelihood will favour simplicity if the underlying data lets itself be represented in simple ways. Interesing isn't it?

Finally, we know that big models typically converge on some flat solution space and that flat solutions are associated with models that generalize well. This becomes pretty intuitive now. Two things are also true about flat subspaces in high dimensions: (i.) these flat subspaces make up a lot of the volume in higher dimensions and (ii.) they are easily compressible. So finding a flat subspace with low loss is good in two ways: (i.) the marginal likelihood will be very high as this is a good solution that also has a lot of probability mass for this solution (i.e. has the right inductive bias); and (ii.) this will be a comparitively simple solution as it many different degenerate hypotheses exist in this flat space and hence the solution is quite compressible. Low training loss and low Kolmogorov complexity! Double win?

Actually it's even better: a flat solution will represent a diverse family of possible solutions which by wisdom of the crowd should result in better predictions. And indeed they do because this is exactly what we do for deep ensembling, retraining the model many times (presumably ending up in the same flat solution space many times) and then averaging. What Wilson shows is something that should feel pretty logical by now, instead of retraining and going the entire SGD route to that solution again and again, we can just skip that and directly marginalize over that flat region, in a method known as MultiSWAG. Deep ensembling is Bayesian deep learning - just less efficient.

One more thing! Just because I learned about this fact for the first time here: Much is made in the ML community about optimization as a universal concept and how SGD dynamics are key to understanding training and also downstream behaviour of models. In fact, you don't need SGD at all. Flat solutions typically cover so much of the volume in high-dimensional space that simpy sampling at random until you find any solution with low training loss will do the trick. A low loss solution is so likely to be a flat solution and hence degenerate and indinstinguishable from the "proper" SGD solution that it will do just as well.

The real questionNow, qu'importe to the practitioner? I think it actually remains an open question whether in a field such as protein folding or molecule generation, where we have some pretty real and universal symmetries, it makes sense to relax these constrains and simply invest in ever larger models. After all, if the restriction bias actually doesn't harm it can help bring down the cost to compute. I think most relevant to my line of work however is a question that Wilson provokes: A given prior over parameters combines with the functional form of a model to induce a distribution over functions that controls the generalization of the model. If we assume this, I think it becomes an urgent question of what prior over parameters and what function class could (ever?) induce a distribution that can model the ragged landscape of activity cliffs that any drug discovery data set will have. Presumably, this should be easier to find for a single target data set, where one class of similar looking compounds have high activity and everything else is flat. But spare a thought for the models trained on data such as the phenotypic screens I did for my previous work on antibiotics discovery where you have many hundreds of actives that target wildly different targets probably in parallel. Such a data set is not only high dimensional but composed of many isolated peaks and much empty land between. Interesting to think that finding the right prior over parameters (the right support) and the right class of models (right inductive bias) might just hold the key for properly generalizable AI for drug discovery.

← Back to main.